Two Pounds of Pork and Five Pounds of Beef. Ratio of Marginal Utility

Chapter 33. International Trade

33.i Absolute and Comparative Advantage

Learning Objectives

Past the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Ascertain absolute advantage, comparative advantage, and opportunity costs

- Explain the gains of trade created when a land specializes

The American statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) once wrote: "No nation was ever ruined by trade." Many economists would express their attitudes toward international merchandise in an even more positive way. The evidence that international trade confers overall benefits on economies is pretty strong. Trade has accompanied economic growth in the United States and around the world. Many of the national economies that take shown the most rapid growth in the last few decades—for example, Nihon, South Korea, Cathay, and India—take done so by dramatically orienting their economies toward international merchandise. There is no mod example of a country that has shut itself off from world trade and nevertheless prospered. To sympathize the benefits of trade, or why we merchandise in the first place, nosotros demand to empathise the concepts of comparative and absolute advantage.

In 1817, David Ricardo, a businessman, economist, and fellow member of the British Parliament, wrote a treatise chosen On the Principles of Political Economy and Revenue enhancement. In this treatise, Ricardo argued that specialization and free trade benefit all trading partners, even those that may be relatively inefficient. To run across what he meant, we must be able to distinguish between accented and comparative advantage.

A state has an absolute advantage in producing a good over some other country if information technology uses fewer resources to produce that practiced. Absolute advantage tin be the result of a country's natural endowment. For example, extracting oil in Kingdom of saudi arabia is pretty much only a matter of "drilling a pigsty." Producing oil in other countries can require considerable exploration and costly technologies for drilling and extraction—if indeed they have any oil at all. The The states has some of the richest farmland in the world, making it easier to abound corn and wheat than in many other countries. Guatemala and Colombia have climates especially suited for growing coffee. Chile and Zambia have some of the world's richest copper mines. As some take argued, "geography is destiny." Chile will provide copper and Guatemala will produce java, and they will trade. When each country has a product others need and it tin can be produced with fewer resource in one country over another, then it is like shooting fish in a barrel to imagine all parties benefitting from trade. However, thinking about merchandise but in terms of geography and accented advantage is incomplete. Trade really occurs considering of comparative advantage.

Recall from the chapter Pick in a World of Scarcity that a country has a comparative advantage when a good can exist produced at a lower cost in terms of other appurtenances. The question each country or company should be asking when it trades is this: "What do we give up to produce this good?" Information technology should be no surprise that the concept of comparative advantage is based on this idea of opportunity cost from Choice in a Earth of Scarcity. For example, if Zambia focuses its resources on producing copper, its labor, land and financial resources cannot exist used to produce other goods such as corn. As a result, Zambia gives upward the opportunity to produce corn. How do we quantify the cost in terms of other goods? Simplify the problem and assume that Republic of zambia just needs labor to produce copper and corn. The companies that produce either copper or corn tell you that it takes ten hours to mine a ton of copper and 20 hours to harvest a bushel of corn. This means the opportunity cost of producing a ton of copper is 2 bushels of corn. The side by side department develops accented and comparative advantage in greater detail and relates them to merchandise.

Visit this website for a list of articles and podcasts pertaining to international trade topics.

A Numerical Instance of Accented and Comparative Reward

Consider a hypothetical earth with two countries, Saudi Arabia and the U.s., and two products, oil and corn. Further presume that consumers in both countries desire both these goods. These goods are homogeneous, meaning that consumers/producers cannot differentiate betwixt corn or oil from either country. At that place is simply one resource available in both countries, labor hours. Saudi Arabia tin can produce oil with fewer resources, while the United States can produce corn with fewer resources. Table 1 illustrates the advantages of the two countries, expressed in terms of how many hours information technology takes to produce one unit of each good.

| Country | Oil (hours per barrel) | Corn (hours per bushel) |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 4 |

| United States | 2 | i |

| Table 1. How Many Hours It Takes to Produce Oil and Corn | ||

In Table i, Saudi arabia has an accented advantage in the production of oil considering information technology but takes an hr to produce a barrel of oil compared to two hours in the Us. The United States has an absolute advantage in the production of corn.

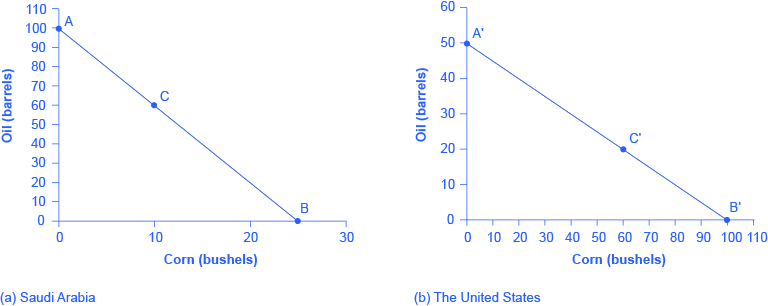

To simplify, allow'due south say that Saudi Arabia and the United states of america each have 100 worker hours (see Table 2). We illustrate what each country is capable of producing on its own using a product possibility frontier (PPF) graph, shown in Effigy ane. Recall from Pick in a World of Scarcity that the production possibilities frontier shows the maximum amount that each land can produce given its express resource, in this case workers, and its level of technology.

| Country | Oil Production using 100 worker hours (barrels) | Corn Production using 100 worker hours (bushels) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 100 | or | 25 |

| United States | 50 | or | 100 |

| Tabular array two. Production Possibilities before Trade | |||

Arguably Saudi and U.S. consumers desire both oil and corn to live. Let's say that before trade occurs, both countries produce and consume at point C or C'. Thus, before trade, the Saudi Arabian economic system volition devote 60 worker hours to produce oil, as shown in Table 3. Given the information in Table one, this choice implies that it produces/consumes 60 barrels of oil. With the remaining 40 worker hours, since it needs four hours to produce a bushel of corn, it tin can produce just ten bushels. To be at point C', the U.S. economy devotes 40 worker hours to produce 20 barrels of oil and the remaining worker hours can exist allocated to produce sixty bushels of corn.

| State | Oil Product (barrels) | Corn Product (bushels) |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia (C) | 60 | 10 |

| United states (C') | 20 | 60 |

| Total World Production | lxxx | 70 |

| Table 3. Production earlier Trade | ||

The slope of the production possibility frontier illustrates the opportunity cost of producing oil in terms of corn. Using all its resource, the United States can produce 50 barrels of oil or 100 bushels of corn. So the opportunity cost of ane barrel of oil is two bushels of corn—or the slope is 1/two. Thus, in the U.South. production possibility frontier graph, every increase in oil product of one barrel implies a subtract of two bushels of corn. Saudi Arabia can produce 100 barrels of oil or 25 bushels of corn. The opportunity price of producing one barrel of oil is the loss of one/4 of a bushel of corn that Saudi workers could otherwise have produced. In terms of corn, notice that Saudi Arabia gives upward the to the lowest degree to produce a barrel of oil. These calculations are summarized in Table iv.

| Country | Opportunity cost of one unit of measurement — Oil (in terms of corn) | Opportunity cost of 1 unit — Corn (in terms of oil) |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | ¼ | 4 |

| United States | ii | ½ |

| Tabular array 4. Opportunity Toll and Comparative Advantage | ||

Again remember that comparative advantage was defined as the opportunity cost of producing appurtenances. Since Kingdom of saudi arabia gives up the least to produce a butt of oil, (1414 < 22 in Tabular array 4) information technology has a comparative reward in oil production. The United States gives upward the least to produce a bushel of corn, so it has a comparative advantage in corn production.

In this example, at that place is symmetry between accented and comparative advantage. Saudi Arabia needs fewer worker hours to produce oil (absolute reward, run across Tabular array 1), and also gives upwards the least in terms of other goods to produce oil (comparative advantage, run across Tabular array 4). Such symmetry is not ever the case, every bit nosotros will testify after nosotros accept discussed gains from trade fully. Merely first, read the following Clear It Upwards feature to make certain yous understand why the PPF line in the graphs is straight.

Tin can a production possibility borderland be directly?

When you first met the product possibility frontier (PPF) in the chapter on Pick in a World of Scarcity information technology was drawn with an outward-bending shape. This shape illustrated that as inputs were transferred from producing one skilful to another—like from education to wellness services—at that place were increasing opportunity costs. In the examples in this chapter, the PPFs are drawn as directly lines, which ways that opportunity costs are abiding. When a marginal unit of labor is transferred away from growing corn and toward producing oil, the decline in the quantity of corn and the increment in the quantity of oil is ever the same. In reality this is possible only if the contribution of boosted workers to output did not change as the scale of product inverse. The linear product possibilities frontier is a less realistic model, but a straight line simplifies calculations. It also illustrates economic themes like accented and comparative advantage simply as clearly.

Gains from Trade

Consider the trading positions of the United States and Saudi Arabia later they accept specialized and traded. Before trade, Saudi Arabia produces/consumes sixty barrels of oil and 10 bushels of corn. The U.s.a. produces/consumes 20 barrels of oil and 60 bushels of corn. Given their current production levels, if the United States tin trade an corporeality of corn fewer than 60 bushels and receives in exchange an amount of oil greater than xx barrels, information technology will gain from merchandise. With trade, the United States tin can consume more of both goods than it did without specialization and trade. (Recollect that the chapter Welcome to Economic science! divers specialization as it applies to workers and firms. Specialization is as well used to depict the occurrence when a state shifts resources to focus on producing a proficient that offers comparative reward.) Similarly, if Saudi Arabia can trade an amount of oil less than 60 barrels and receive in commutation an amount of corn greater than 10 bushels, it volition have more than of both appurtenances than information technology did before specialization and trade. Table 5 illustrates the range of trades that would benefit both sides.

| The U.S. Economy, subsequently Specialization, Volition Benefit If It: | The Saudi Arabian Economy, after Specialization, Will Benefit If It: |

|---|---|

| Exports no more than 60 bushels of corn | Imports at to the lowest degree 10 bushels of corn |

| Imports at to the lowest degree 20 barrels of oil | Exports less than threescore barrels of oil |

| Table 5. The Range of Trades That Benefit Both the The states and Saudi Arabia | |

The underlying reason why trade benefits both sides is rooted in the concept of opportunity toll, as the following Clear It Up characteristic explains. If Saudi arabia wishes to aggrandize domestic production of corn in a world without international trade, then based on its opportunity costs it must give upward iv barrels of oil for every one additional bushel of corn. If Saudi Arabia could find a way to give up less than four barrels of oil for an additional bushel of corn (or equivalently, to receive more than i bushel of corn for 4 barrels of oil), it would be better off.

What are the opportunity costs and gains from trade?

The range of trades that volition benefit each country is based on the country's opportunity cost of producing each good. The Us can produce 100 bushels of corn or 50 barrels of oil. For the United States, the opportunity cost of producing one butt of oil is two bushels of corn. If we dissever the numbers in a higher place by 50, we become the same ratio: one barrel of oil is equivalent to two bushels of corn, or (100/50 = 2 and 50/50 = 1). In a trade with Saudi Arabia, if the United States is going to requite up 100 bushels of corn in exports, it must import at least 50 barrels of oil to be just likewise off. Clearly, to proceeds from trade it needs to be able to gain more than a one-half barrel of oil for its bushel of corn—or why trade at all?

Call up that David Ricardo argued that if each country specializes in its comparative advantage, it will benefit from trade, and total global output volition increase. How can we show gains from merchandise every bit a result of comparative advantage and specialization? Table 6 shows the output assuming that each country specializes in its comparative advantage and produces no other good. This is 100% specialization. Specialization leads to an increase in total globe production. (Compare the total world production in Tabular array three to that in Table 6.)

| Country | Quantity produced after 100% specialization — Oil (barrels) | Quantity produced later 100% specialization — Corn (bushels) |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi arabia | 100 | 0 |

| United States | 0 | 100 |

| Total Earth Production | 100 | 100 |

| Table 6. How Specialization Expands Output | ||

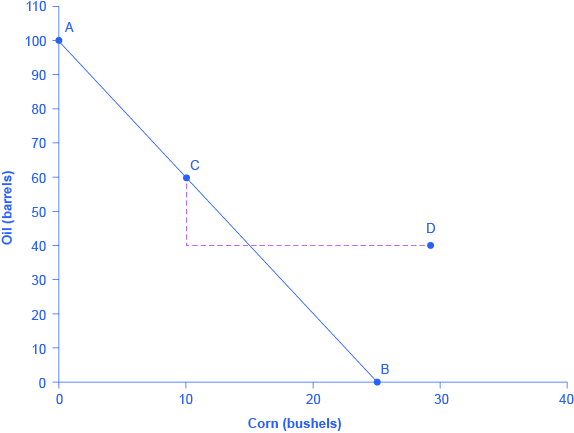

What if nosotros did not have consummate specialization, as in Tabular array 6? Would at that place still be gains from trade? Consider another example, such every bit when the United States and Saudi Arabia first at C and C', respectively, as shown in Figure 1. Consider what occurs when trade is allowed and the Us exports 20 bushels of corn to Saudi Arabia in exchange for twenty barrels of oil.

Starting at point C, reduce Saudi Oil product by 20 and commutation it for xx units of corn to reach point D (see Figure 2). Notice that even without 100% specialization, if the "trading cost," in this case twenty barrels of oil for twenty bushels of corn, is greater than the country'southward opportunity cost, the Saudis volition gain from merchandise. Indeed both countries consume more of both goods after specialized production and trade occurs.

Visit this website for trade-related information visualizations.

Cardinal Concepts and Summary

A country has an absolute advantage in those products in which it has a productivity edge over other countries; information technology takes fewer resource to produce a product. A country has a comparative advantage when a proficient can be produced at a lower toll in terms of other goods. Countries that specialize based on comparative advantage gain from trade.

Self-Check Questions

- True or False: The source of comparative advantage must exist natural elements similar climate and mineral deposits. Explicate.

- Brazil can produce 100 pounds of beef or 10 autos; in contrast the U.s. can produce 40 pounds of beef or 30 autos. Which land has the absolute advantage in beef? Which land has the absolute advantage in producing autos? What is the opportunity cost of producing one pound of beefiness in Brazil? What is the opportunity price of producing 1 pound of beef in the Us?

- In French republic information technology takes ane worker to produce one sweater, and i worker to produce i bottle of wine. In Tunisia it takes two workers to produce one sweater, and 3 workers to produce one bottle of vino. Who has the accented reward in production of sweaters? Who has the absolute advantage in the product of wine? How can you tell?

Review Questions

- What is absolute reward? What is comparative advantage?

- Under what conditions does comparative reward lead to gains from merchandise?

- What factors does Paul Krugman identify that supported the expansion of international trade in the 1800s?

Critical Thinking Questions

- Are differences in geography backside the differences in absolute advantages?

- Why does the Us not accept an accented advantage in coffee?

- Look at Self-Check Question iii. Compute the opportunity costs of producing sweaters and wine in both France and Tunisia. Who has the lowest opportunity price of producing sweaters and who has the everyman opportunity cost of producing wine? Explicate what information technology means to accept a lower opportunity cost.

Issues

French republic and Tunisia both have Mediterranean climates that are excellent for producing/harvesting green beans and tomatoes. In France it takes 2 hours for each worker to harvest green beans and two hours to harvest a love apple. Tunisian workers need only one hr to harvest the tomatoes only four hours to harvest green beans. Assume there are only two workers, ane in each country, and each works 40 hours a week.

- Draw a product possibilities borderland for each country. Hint: Retrieve the production possibility frontier is the maximum that all workers can produce at a unit of measurement of time which, in this problem, is a calendar week.

- Identify which country has the accented advantage in light-green beans and which land has the accented advantage in tomatoes.

- Place which land has the comparative reward.

- How much would France have to give up in terms of tomatoes to gain from merchandise? How much would it take to give up in terms of green beans?

References

Krugman, Paul R. Pop Internationalism. The MIT Press, Cambridge. 1996.

Krugman, Paul R. "What Do Undergrads Need to Know nearly Trade?" American Economic Review 83, no. 2. 1993. 23-26.

Ricardo, David. On the Principles of Political Economic system and Taxation. London: John Murray, 1817.

Ricardo, David. "On the Principles of Political Economy and Revenue enhancement." Library of Economic science and Liberty. http://www.econlib.org/library/Ricardo/ricP.html.

Glossary

- accented advantage

- when ane country tin can use fewer resource to produce a practiced compared to some other state; when a country is more productive compared to another country

- gain from trade

- a land that can consume more than than it tin can produce every bit a event of specialization and trade

Solutions

Answers to Self-Check Questions

- False. Anything that leads to different levels of productivity between two economies tin can be a source of comparative advantage. For example, the education of workers, the cognition base of engineers and scientists in a land, the part of a split-up value chain where they accept their specialized learning, economies of scale, and other factors tin can all determine comparative advantage.

- Brazil has the absolute advantage in producing beef and the United States has the absolute reward in autos. The opportunity cost of producing one pound of beef is 1/10 of an car; in the U.s. it is 3/4 of an auto.

- In answering questions similar these, it is often helpful to begin by organizing the information in a table, such every bit in the following table. Notice that, in this case, the productivity of the countries is expressed in terms of how many workers it takes to produce a unit of measurement of a product.

Country I Sweater One Bottle of vino France 1 worker 1 worker Tunisia ii workers 3 workers Table seven. In this example, France has an accented advantage in the production of both sweaters and wine. You can tell because it takes France less labor to produce a unit of the good.

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/principlesofeconomics/chapter/33-1-absolute-and-comparative-advantage/

Post a Comment for "Two Pounds of Pork and Five Pounds of Beef. Ratio of Marginal Utility"